Connor Ruebusch Breaks Down Amanda Nunes, How Good Is the GOAT?

In the UFC, GOATs come and go. Fans coined the term “GOAT,” mostly to give the old pound-for-pound debate a weekend off, but from the promotion’s point of view it’s just another marketing buzzword. Someone in hair and makeup whispers to Joe Rogan that they think Renan Barao might be the GOAT, and he marches off to the booth swollen with unwarranted hype, soundbites already falling from his mouth, totally unaware that he’ll forget it all by the time another pay-per-view needs selling.

At this point, it’s less the Greatest of All Time and more the Greatest of All Time… of the Week.

Now UFC 289 is around the corner, and wouldn’t you know it, we’ve got another GOAT. At least, in Amanda Nunes’ case, the UFC is usually careful to refer to her as the greatest female fighter in MMA history, but even that raises questions about what greatness really means. How good does a GOAT have to be?

So, today we’re going to be a bit critical of the Lioness. This is not to disparage Nunes, nor even to claim definitively that she is not the greatest female fighter of all time, which, all things being relative, she may very well be. Rather, our goal is to peel the mask of UFC marketing away from the true face of a fighter who should not need any exaggeration to be interesting. We want to paint a more accurate picture of the UFC women’s bantamweight champion, and the division that is her domain, and fight back against the flattening of what it means to be great.

Because yes, Amanda Nunes is great–but she damn sure ain’t great at everything.

The Basics

It should go without saying: the greatest fighter of all time, whatever other qualifiers you might attach to that title, should have a mastery of fundamental technique.

Georges St-Pierre, Jose Aldo, Anderson Silva, Jon Jones, Demetrious Johnson–no one could accuse any of these fighters of lacking in fundamentals. They all move their feet well, they all work the jab. They feint, they defend, they manage distance and control the cage. None of these fighters was perfect in their time, but none of them collapsed when the going got tough, because they knew what to do to survive. When pushed to the brink, their fundamentals served as a safety net.

In December of 2021, Amanda Nunes took on Julianna Pena in defense of her belt. It was just another in a long line of layups–so much so that Nunes herself appeared not to take the challenge very seriously.

That proved to be her undoing. After knocking Pena down early in the first round, Nunes controlled her on the ground, even pausing in a headlock to flash a grin at her corner. Another one, she seemed to say. How pathetic.

But when round two rolled around, Pena proved unwilling to go along with Nunes’ narrative. She met Nunes in the center of the cage. When Amanda stepped in with an overzealous jab, Pena met her with a jab of her own. She proceeded to press forward. Almost immediately, Nunes’ nerves began to fray. She started charging toward Pena, trying with brute force to dissuade her from pressuring. Pena was not deterred. She continued to meet every one of Nunes’ attacks with her own–ugly, wide counters that nonetheless had an effect.

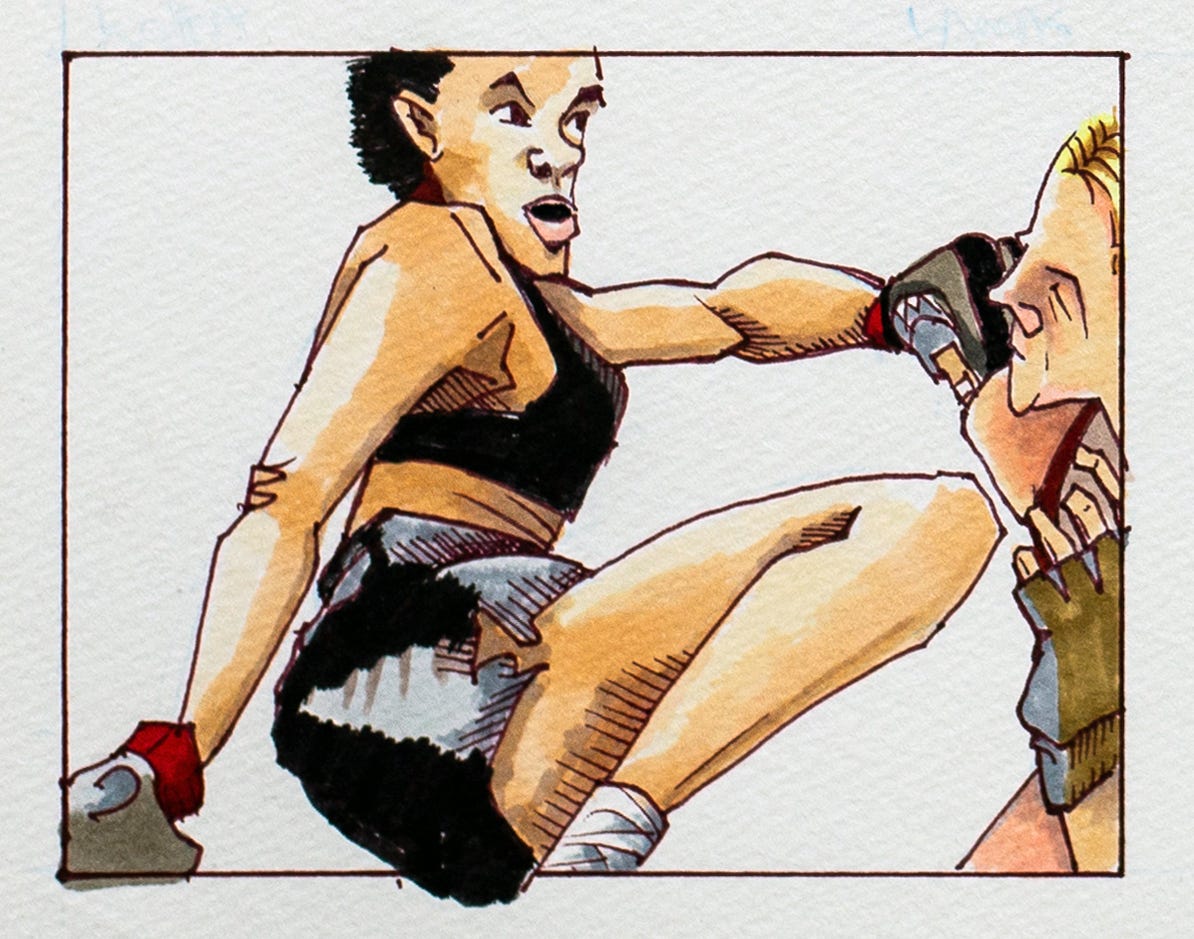

Nunes could not change course. She continued swinging for the fences, even though every attempt to attack resulted in an exchange, and each exchange went worse than the last. It wasn’t yet three minutes into the second round, and Nunes was clearly running out of gas. And then this happened.

1. Battered and exhausted, Nunes lines up on Pena…

2. …and fires a telegraphed jab. Pena slips while firing a jab of her own, and wins the exchange.

3. Nunes finds herself on a new angle.

4. She steps in with another jab, and again Pena easily times her with her own jab.

5. Nunes is clearly confused by what is happening. Is she going to cook up another idea?

6. No. Again Nunes jabs, still telegraphing her shot, stepping in hard and making no effort to disguise her intentions. Pena jabs with her, and wins.

7. Nunes has been pivoting with these jabs. She now finds herself on a strong angle. She should be able to get the jab home from this position, easily penetrating Pena’s wide open stance.

8. But she doesn’t. Again Nunes telegraphs the attack, and Pena makes up for poor position by simply timing what is, at this point, a laughably predictable jab.

9. Disheartened, Nunes tries to think of something else to do.

10. She tries a wild right hand, but the attack is completely unjustified. A different idea, yes, but one for which she has created no particular opening. Pena avoids it almost by accident.

The greatest female fighter of all time, flummoxed… by a jab.

Nunes didn’t just get caught by Pena’s jab. Jabs connect. That’s what they do.

No, the concerning thing was how Nunes got caught by the jab, and how frequently. In the above sequence, Nunes had all manner of options at her disposal. She could have feinted, looking to draw that jab out and then punish it. She did not. She could have moved her head as she exchanged jabs, as Pena did. She could have simply reset, used a little footwork to make Pena move and then started fresh, or raised her right hand to deflect the counter jab, or… anything, really.

Every one of these plans was beyond Nunes’ grasp. Once the momentum shifted, Nunes was unable to reverse it, and her fundamentals, such as they are, abandoned her.

Doing Less

The loss to Pena brought back to the fore a character flaw Nunes had kept hidden for the better part of five years, so much so that many people (including myself) assumed that she had gotten over it entirely. Of course, people do not change that easily. Fighting style is deeply intertwined with innate personality traits, and the worst flaws are not easily cured. A bandaid is all most fighters ever manage.

For Nunes, the problem is clear: she hates pushback. Don’t let the maniac grin fool you: Nunes is not a fighter who thrives under pressure. Rather, the more pressure she receives from her opponent, the greater her need to finish them grows.

Amanda Nunes is a brawler, in other words–down to her very core. She doesn’t brawl because she likes to brawl, but rather the opposite. It’s an instinct born of insecurity. A coping mechanism.

“My mother used to box,” Amanda once told MMA Fighting’s Guilherme Cruz, “and I followed her footsteps into training. She loves fighting… She always says, ‘the first strike has to be yours. She can’t touch you before you touch her. You have to intimidate her.’”

And that, right there, is the philosophy that guided Nunes through the ups and downs of her early career: get her before she gets you. It’s a mindset one short hop away from outright panic. If Nunes were comfortable brawling, as some fighters are, she’d be able to do it for more than a round or two–but she isn’t, and she can’t. Drag the brawler back out of her, as Pena did at UFC 269, and it becomes a question of whether Nunes can finish the fight before she finishes herself.

But where were those instincts hidden away these last five years? It’s clear Nunes didn’t get rid of them entirely. So what was the bandaid?

The answer, like much of Nunes’ game, is deceptively straightforward: she learned to do less. The logic is easy to understand: if every one of Nunes’ losses was orchestrated by her own desperation to crush her opponent, then what if she played her obvious physical advantages a little closer to the vest? If she was prone to pushing a pace she could not maintain, then why not stop pushing the pace altogether?